Oakland has a new proposal to rezone lots of land in the city for additional density. We took a close look at these proposals recently and wanted to highlight where Oakland is on the right track and where it is doubling down on ugly patterns of exclusion.

These rezonings are part of Oakland’s “Housing Element,” a state requirement where Oakland must show it is feasible to add 26,251 new homes throughout the city by 2031. Draft housing elements are submitted to the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) for comment and final approval. A city that fails to obtain final approval from HCD exposes itself to significant risk, including loss of state affordable housing funds and zoning overrides for projects that provide 20% low-income or 100% moderate-income units aka the builder’s remedy.

College Avenue looking towards Rockridge BART

The rezoning proposals fall into five main categories: 1) Affordable Housing Overlay (AHO); 2) by-right approvals for housing element sites; 3) Rockridge District Rezonings; and 4) commercial corridor height increases; and 5) Missing Middle Program.

The Good

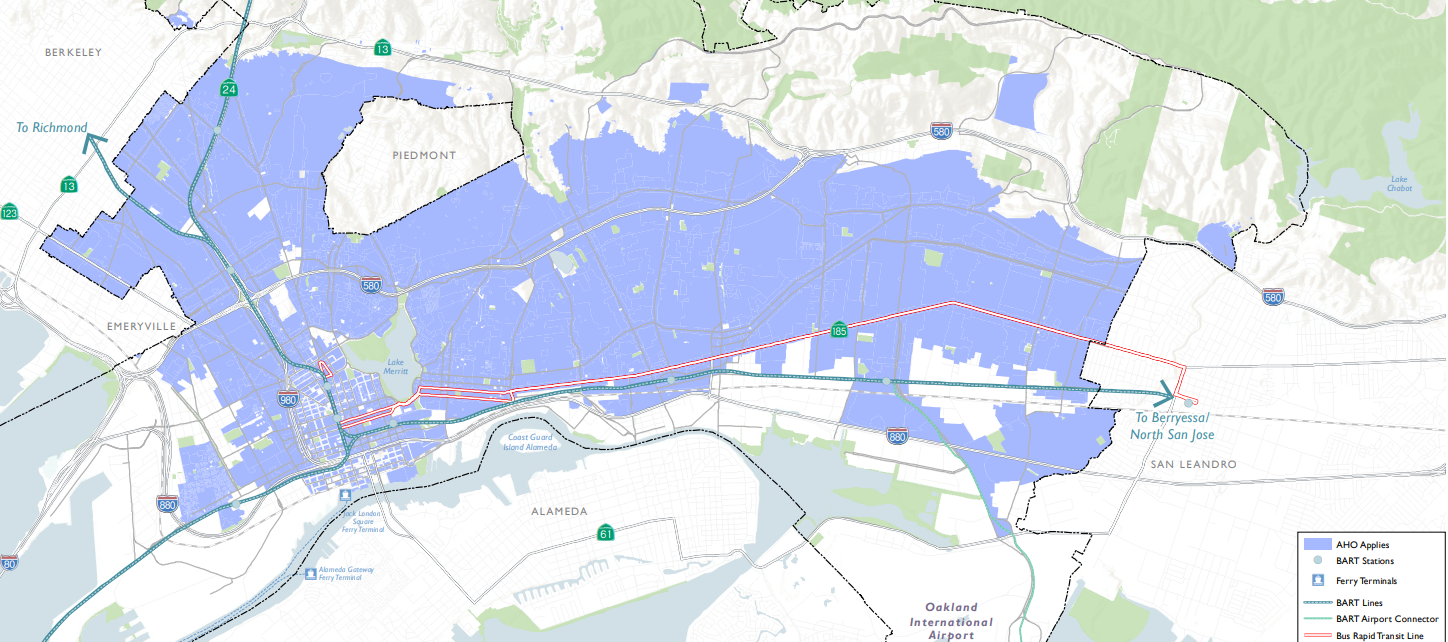

East Bay for Everyone is excited about the proposed affordable housing overlay and by-right approvals. An AHO is one of the key demands EB4E made in its February 2022 letter to the Planning Department. As written, this AHO would allow unlimited density within the physical building standards of the planning code and provide up to 2 stories of height bonuses for housing developments with at least 80% low-income units throughout much of Oakland. This includes high-resource areas in North Oakland and above I-580 as well as single-family districts. In addition, affordable housing projects using the AHO would be approved by-right by Oakland planners, and not subject to risky appeals and litigation.

While there are exclusions for the Very High Severity Fire Zones as well as limitations on height bonuses within historic Areas of Primary Importance we believe that – with a few minor tweaks – Oakland’s AHO could be one of the best tools in the country at delivering low-income homes quickly and equitably.

AHO Map

We are also encouraged by the by-right approvals proposal. Under the proposal, projects on identified housing element sites that provide 20% low-income units would be approved by-right. This allows for certainty for developers as well as providing economic integration in new development.

The Bad

The Missing Middle Program responds to a March 2021 directive from the Oakland City Council to the Planning Department to develop proposals to eliminate single-family zoning and allow for 2-4 units on all residential lots. EB4E started a campaign called “End the Apartment Ban” to eliminate single-family zoning in Berkeley and Oakland in 2019, so we were excited to see this idea develop.

As written, the proposal would allow at least two units in all residential zones, decreases Oakland minimum lot sizes in many residential zones down to 2,500 sqft and marginally increases allowable densities in several residential zones. Importantly the proposal eliminates conditional use permits for residential zones, which would make conforming projects within the developable envelope by-right – applicants wouldn’t need to win a vote at City Hall to build a project. Finally, the proposal would rezone certain areas throughout Oakland to marginally more intensive use (e.g. Cleveland Heights goes from RD-1 to RD-2).

There are several key flaws to highlight. First, the minimum lot size decrease in many categories makes Oakland’s plan more restrictive than the state’s SB 9 duplex bill – which allows 1,200 sqft in most circumstances. Given that SB 9 only applies to certain residential parcels zoned for a single unit, this proposal may in fact represent an effective downzoning of the current 1,200 sqft minimum lot size to 2,500 sqft.

Second, based on the proposed density requirements (e.g. 1,500 sqft of lot per unit in RM-2) the ability to build more than two units on many typical lots – even near transit is unlikely. Paired with decisions to limit or fail to even rezone to higher intensity in high-resource and higher rent places like Lower Rockridge, Temescal, Trestle Glen and Crocker Highlands the proposal is unlikely to yield many 3 or 4 unit projects at all.

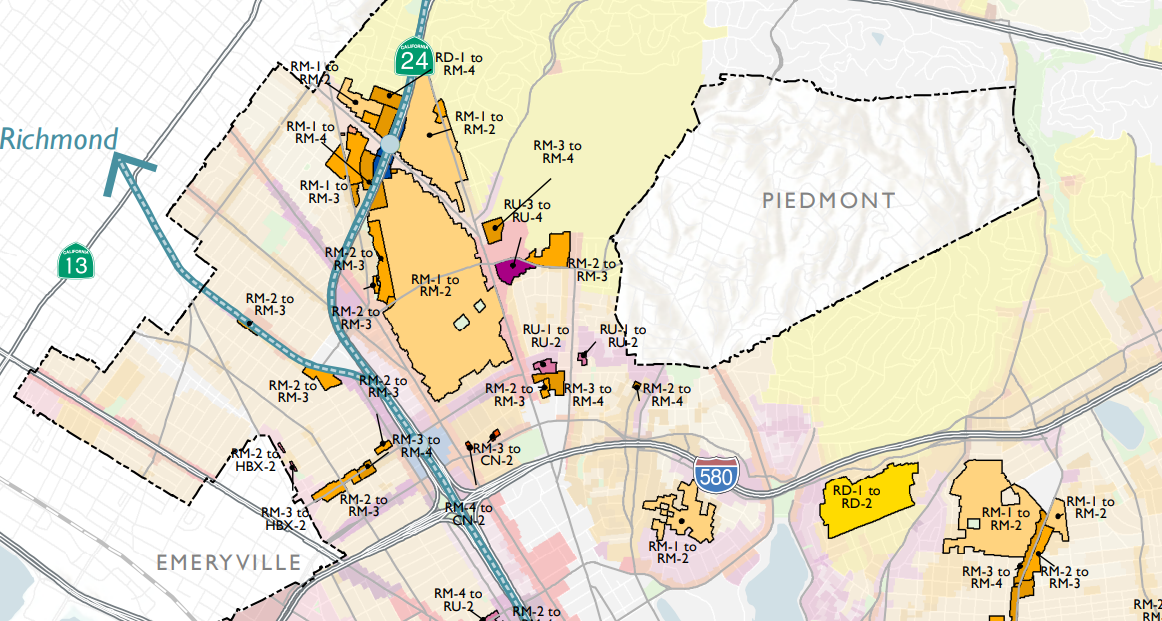

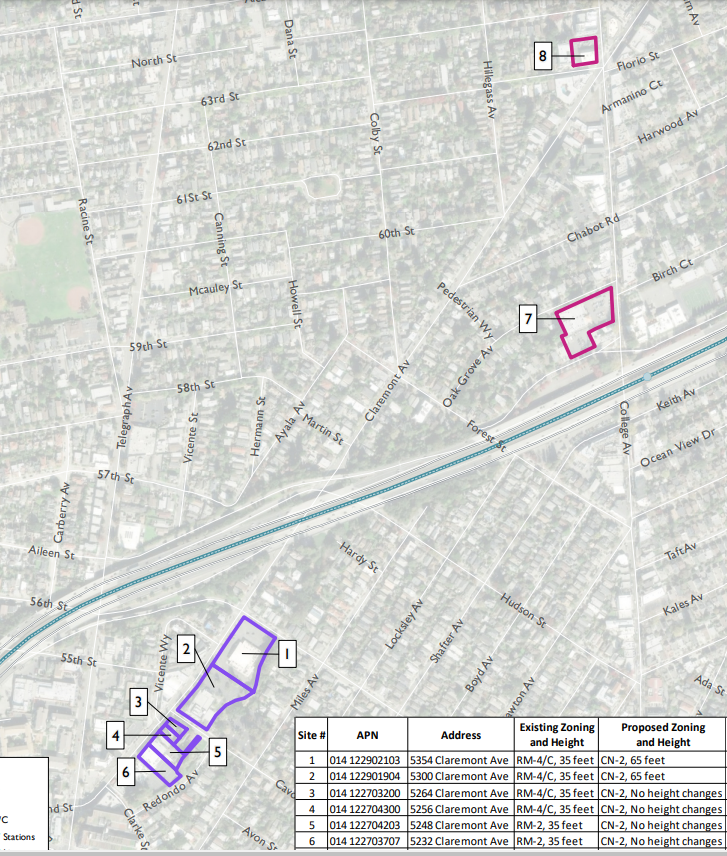

Rezoning Map of North Oakland

Third, Oakland is keeping the same rules about setbacks and parking requirements. Failure to address development standards is one of the primary reasons Minneapolis failed to see much missing middle development since it eliminated single-family zoning in 2019. Portland, through its Residential Infill Project, recognized this mistake and allowed multifamily applications to get additional floor area compared with single family home applications– ensuring small apartment proposals would be financially competitive with McMansions. Additionally, the proposal here does not reduce off-street parking requirements for 2-4 unit projects. This is especially problematic because small projects cannot afford to dig down to build underground parking.

Overall, we think the Missing Middle Program can be significantly strengthened by addressing these concerns to deliver attainable rental and ownership housing opportunities for Oaklanders.

The Ugly

We are most concerned with the Rockridge rezonings and commercial corridor rezonings, which can both be found here towards the end of the pdf. Rockridge is one of the highest resource areas in Oakland and has access to a BART station, AC Transit lines, parks and other services. These are opportunities that East and West Oakland residents have been deprived of due to decades of redlining, disinvestment, electoral disenfranchisement and other structural racist and extractive processes. According to research by the UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute Rockridge is one of the most highly-segregated “whites-only” tracts in Alameda County.

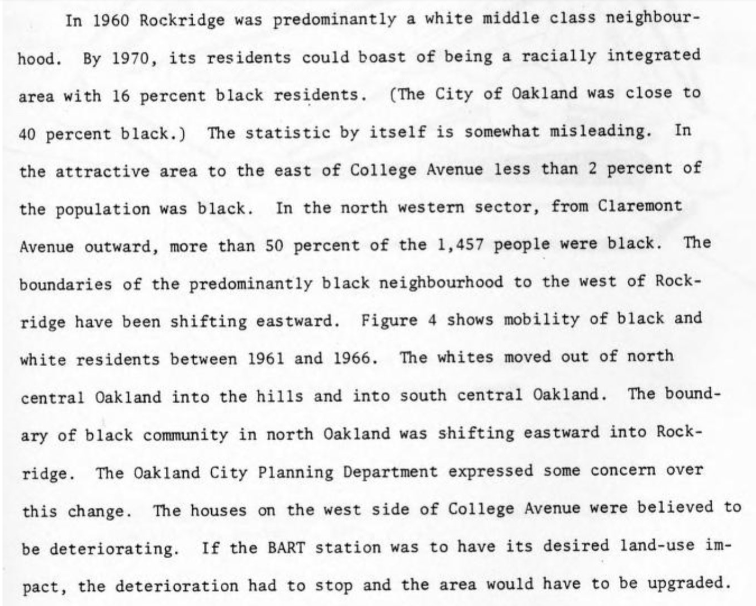

Description of demographic patterns in Rockridge and nearby in the 1960s and early 1970s

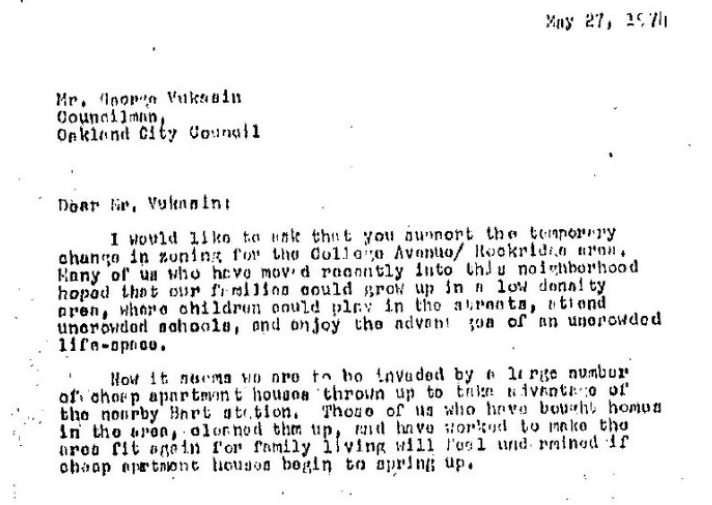

This isn’t accidental. Rockridge was a racially-restricted neighborhood since its development post-1906 to late 1920s until passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which outlawed racial discrimination in housing. Rockridgers embarked on a coordinated campaign in the late 1960s and 1970s to eliminate multifamily housing options in the neighborhood after growing numbers of Black residents broke the color line and moved near or to Rockridge after construction of the Grove-Shafter Freeway, BART and other urban renewal projects.

1974 letter from Rockridge homeowner complaining of invasion of apartments

By 1971 Rockridgers succeeded in stopping plans for transit-oriented development around the new BART station. In 1973 39 units of low-income senior housing opened on Manila Avenue – SAHA’s Otterbein Manor on College Ave was the last newly constructed affordable housing project in Rockridge – it is 49 years old. In 1974 the Oakland City Council, at the urging of Rockridge residents, passed legislation downzoning nearly all residential areas within Rockridge to single-family only and College Avenue to commercial use with a 35’ height limit. Little has changed since then. In the past 15 years a mixed-income, transit-oriented development plan has been developed and implemented at every Oakland BART station except for Rockridge.

In an effort to right these wrongs, EB4E launched an #UpzoneRockridge campaign in 2017. We have pushed for a planning process for mixed-income and affordable housing as well as supporting individual projects such as CCA in Rockridge. As part of the Housing Element process EB4E noted Oakland’s failure to rezone Rockridge as part of its Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rezonings in its initial draft housing element. HCD also noted Oakland’s failure to rezone Rockridge in its rejection of Oakland’s initial draft.

Oakland has now produced a Rockridge rezoning proposal. Unfortunately the proposal will produce very little housing and may even incentivize displacement. The Planning Department proposes to rezone 8 sites to help facilitate redevelopment into new housing. A sample of the sites:

- The Department of Motor Vehicles on Claremont

- Trader Joe’s parking lot

- A clinic owned by UCSF

- 42 units of rent-controlled housing

Proposed Rockridge Rezonings

These sites are unlikely to be developed. Large institutions such as the DMV and UCSF are largely indifferent to the potential benefit of developing 20-40 unit buildings given the hassle of relocating their operations. And Trader Joe’s parking lots are already congested as it is. Finally, Oakland should not be in the practice of placing zoned capacity on top of rent-controlled housing in order for it to be demolished and redeveloped. This practice can either lead to direct displacement or is a form of paper upzoning. The latter is more likely the case because these 42 rent-controlled apartments are protected by Senator Nancy Skinner’s SB 8 no-net-loss requirements for rent-controlled housing and would have to be replaced.

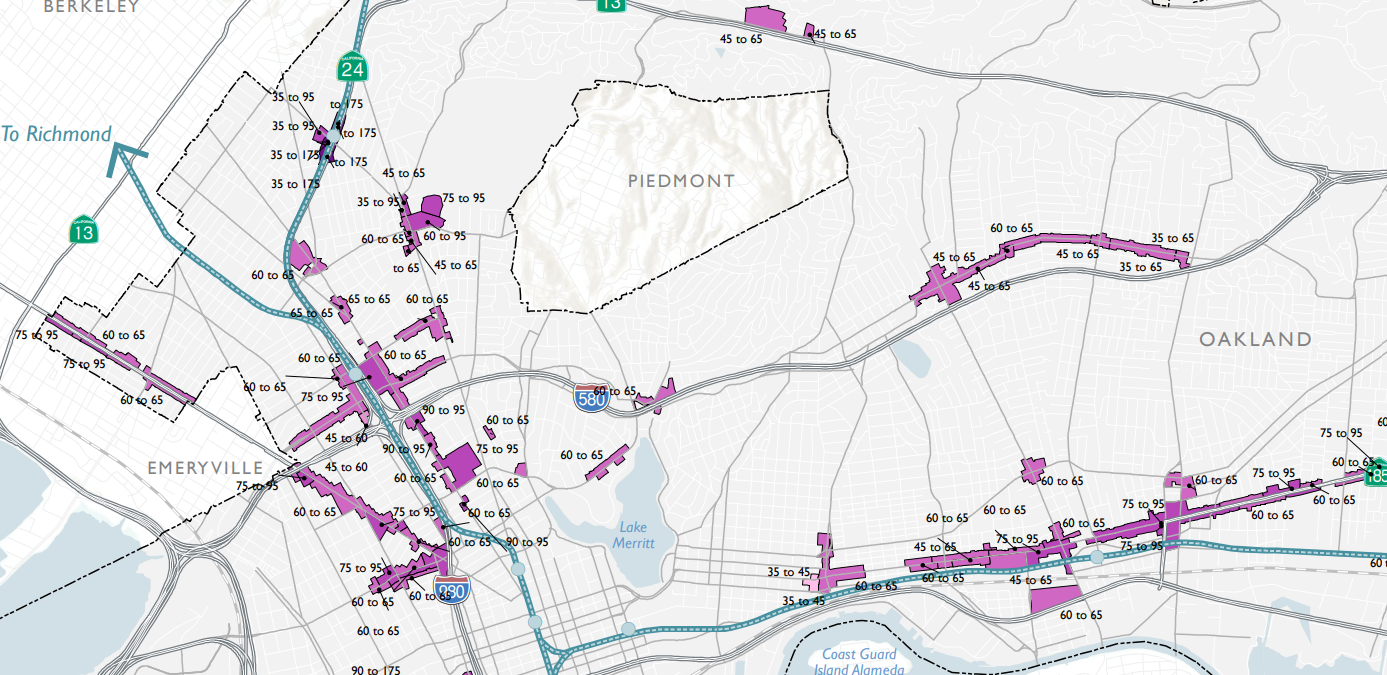

Untouched by the rezonings? The rest of the non-tenant occupied parcels of College Avenue and Claremont Avenue, whose heights remain capped at 35’. It’s clear that the Planning Department is capable of rezoning commercial corridors for greater height and intensity… outside of Rockridge. The Planning Department’s commercial rezonings increase heights of commercial areas throughout West and East Oakland. Miles of International Boulevard have increased heights under the proposal, even to 95’ in Deep East Oakland. 7th Street along West Oakland BART sees height increases up to 175’ and 250’. The Laurel District – over 2 miles from Fruitvale BART – sees its commercial heights go from 35’ to 65’. In what world is it okay for the thriving Laurel District to be rezoned for up to 65’ but College, Claremont and Shattuck a mere ½ mile from BART cannot?

Commercial corridor height changes

To be clear, we think many of the proposed commercial rezonings make sense from a housing, carbon emissions and livability perspective. But it is hard to stomach how extensive and intensive the rezonings are for commercial corridors in West and East Oakland when high-resource areas in North Oakland are almost entirely left untouched. As-is, this proposal reinforces the inequities of the past ten years: housing development concentrated in Oakland’s low and moderate-income neighborhoods while high-resource communities undergo relatively little physical change.

Fortunately there is still time for Oakland policymakers, organizations, and ordinary residents who support equitable housing policies to speak up to make sure that these rezoning proposals are updated to reflect both our collective housing needs and values. The Planning Commission will consider these proposals on October 19, 2022 at 3pm. The Oakland Planning Department will hold additional meetings in November. The message is clear: we can and must do better.