Oakland is updating its general plan over the next several years with a goal of adopting a final General Plan in Winter 2027. The General Plan is a comprehensive document that controls land use but also open space, transportation and infrastructure in order to guide development.

As we’ll get into below, Oakland Planners have laid out an ambitious vision for equitable growth. Unfortunately the framing of the early plan has led many to see the different visions of growth as mutually exclusive – when they need not be and are not. More importantly, however, is that the early plans do not at all address how Oakland will implement these ambitious plans. This is especially critical given Oakland’s poor track record delivering infrastructure, parks and affordable housing.

In brief:

- The plan — if implemented — would reduce vehicles miles traveled, increase transit and active transport mode share, increase equitable access to open space and deliver more housing and jobs.

- Planners need to work on improving the transportation element through coordination with AC Transit and developing cycling/walking connections instead of forcing new buildings to build public parking for cars.

- This ambitious vision is all for naught unless Oakland dramatically reforms how it implements the plan through staffing, coordination and funding changes.

Oakland has not updated its general plan since 1998. That means Oakland, with a few exceptions for neighborhood specific plans, has a planning system that debuted the same year as Windows 98. Much has changed in software since 1998 – the same can be said for Oakland’s economic position, transportation needs, housing cost-burdens and recreational preferences. We need a new operating system for how Oakland develops.

What’s in the Plan

The new General Plan Update seeks to do just that. Oakland Planners bifurcated part of the general plan update process. Phase 1 of the General Plan Update culminated in October 2023 rezonings across the city to comply with the City’s commitments in the adopted housing element. We previously covered these upzonings that include commercial corridor height and density increases, missing middle housing and more development potential in high-resource neighborhoods like Rockridge. Then in late 2024 the Oakland City Council adopted the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan – after a nine (9) year process – to focus housing/jobs, infrastructure, transportation and open space development in Downtown, Lake Merritt office district, Jack London Square and the light industrial area Victory Court.

Phase 2 of the General Plan Update promises a more comprehensive planning framework than land use changes to facilitate housing development. In response to initial community engagement, Oakland planners have released Alternatives to guide deeper discussion by Oaklanders. After reading this blog post – or even better reading the Alternatives yourself – you should participate in the survey as well as provide email or in-person public comment at upcoming opportunities. The comment period closes September 24.

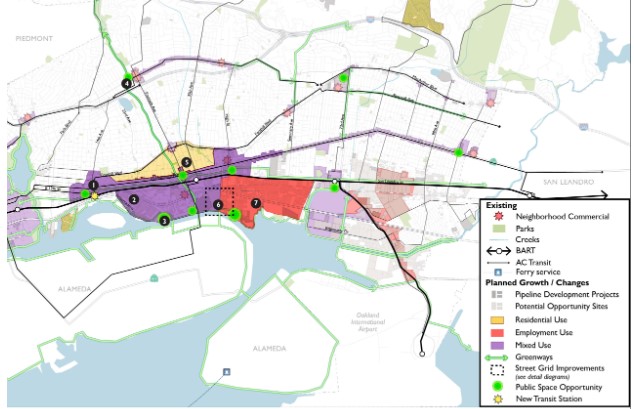

As part of the Alternatives, Oakland planners have laid out a baseline condition and three visions of growth. The baseline condition includes existing neighborhood specific plans, the Phase 1 upzoning and parallel planning processes like Link21’s plan for improved regional rail (BART and standard gauge) and a new electrified standard gauge crossing. The three visions of growth lay out different growth scenarios that are called “options” but are not, per Oakland Planners, mutually exclusive. Despite such assurances some Oaklanders are concerned that the Alternatives frame may unnecessarily lead to the perceptions that these visions are competing and mutually exclusive. Of course staff time and capital resources are limited so we cannot have it all – but there’s no reason we cannot invest in all neighborhoods while also having a San Antonio BART station.

These options are as follows: Neighborhoods, Transit Corridors and Midtown Waterfront.

The Neighborhood Strategy distributes housing and job growth in nodes throughout the city while also adding a series of mid-sized and pocket parks, especially in places underserved with open and recreation space like East Oakland. Transportation improvements are focused in the Neighborhood strategy on active transport safety treatments to make walking and biking safer and more comfortable.

The Transport Strategy focuses growth at BART stations and along higher frequency (10 minute or better) bus lines. More housing and jobs would be clustered at the intersections of these bus lines. The city would also seek to add larger open spaces near these transport corridors. In many ways this strategy has already been adopted by the City. The Phase 1 rezonings included many height and density increases along commercial corridors that host bus service. But several omissions in the Transport strategy are glaring: 51st Street in Rockridge between the high-frequency 6 and 51A routes is omitted from any growth. And the core area around Rockridge BART 51B/51A (12 minute headways) features moderate growth equivalent to or less than that of the Dimond and Laurel Districts served by the 57 (15 minute headways). It’s unclear why neighborhoods 1.75 miles from Fruitvale BART should have 9 story buildings while Rockridge parcels ¼ mile from BART are limited to 4 stories. Oakland Planners insisted on Laurel and Dimond seeing large amounts of growth while Rockridge was shielded in Phase 1 of the General Plan Update, until they relented under pressure from East Bay for Everyone and the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

The Laurel District gets 9 story buildings while Rockridge parcels near BART remain capped at 45’.

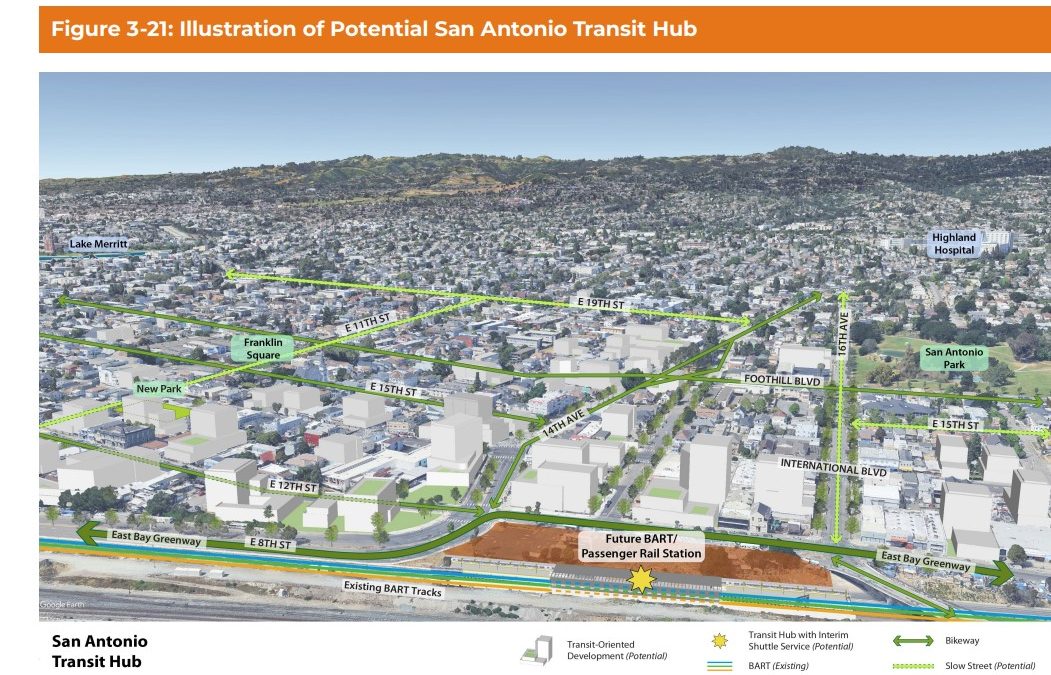

The Midtown Waterfront Strategy is the most ambitious. It concentrates development roughly between Foothill Boulevard and Embarcadero between 14th Avenue and High Street. Legacy light industrial uses would give way to new housing, R&D job growth, new waterfront open space and a San Antonio BART station and connecting multi-use pathways. One of the challenges of this strategy is that I-880 bifurcates the plan area. Another is that many of the parcels are polluted, irregular and supported by an infrastructure that prioritizes large truck movements and freight railroads.

Midtown Waterfront Strategy

How do the three Alternatives in this plan collectively stand up to analysis?

The Good

The Alternatives seek to increase housing, jobs, park space and safe, clean transportation options in Oakland. Each strategy – if implemented – would increase access to high-frequency transit, increase transit and active transport mode share, and reduce vehicles miles traveled.

The Neighborhoods option seeks to add and improve parks to underserved parts of Oakland – including East Oakland. This addresses a key inequity between East Oakland and North Oakland/Lake Merritt-adjacent neighborhoods.

Unlike the 1998 General Plan which sought to preserve “community character” of some neighborhoods, the Neighborhood option here seeks to increase housing, jobs and active transport infrastructure in all neighborhoods. In practice those changes may still be low-rise missing middle structures and neighborhood bike routes but this type of incremental development is sorely needed for a host of reasons.

The Midtown Waterfront option includes the key demand of the community group San Antonio Station Alliance: a BART station at 14th Avenue. East Bay for Everyone is a strong supporter of a San Antonio BART station. If this goal is adopted into the Preferred Alternative, it will unlock planning dollars for BART to seriously pursue this infill station.

The Midtown Waterfront option includes a new greenway connection that connects to Sausal Creek in Dimond Park and then onto Joaquin Miller. A greenway connection between the estuary and the Oakland Hills to facilitate access to open space has been a dream of Oaklanders for over 125 years (see chapter 4 – The Politics of Parks by Mitchell Schwarzer).

The Bad

The Alternatives continue to largely shield high-resource neighborhoods near transit and open space from growth. Rockridge, Trestle Glen, Lakeshore and Piedmont Avenue are largely untouched – even in the Neighborhood scenario.

The Alternatives make no mention of removing off-street parking minimums citywide (beyond the current ½ mile from BART / BRT stops standard). Removing parking minimums citywide is a pre-condition to ensuring any of these scenarios can be implemented. Off-street parking minimums drive up housing costs, increase car use, decrease transit and active transport mode share and encourage congestion. Peer cities including San Francisco, Berkeley, and San Jose have already repealed them, and Oakland will be behind the curve if this is not taken up.

As an interim step to a San Antonio BART station, Oakland Planners propose a “BART shuttle” to help demonstrate demand. But BART does not run shuttles.

For Brooklyn Basin’s 4k+ units the City in 2006, instead of planning for AC Transit service – required Signature Development to run a free shuttle with 30-minute frequencies. The developer complied but the service is poor, runs at an infrequent 30-minute headway, and the operator discourages non-residents from using it. In August 2025, 5 years after the first building opened and 4 years after Township Commons park opened, 30-minute service to Brooklyn Basin via AC Transit’s 96 Line started.

It’s also unclear what demand could be demonstrated by a free, but likely infrequent shuttle, which would be far less convenient and attractive than BART or bus service. The fixation on an ad hoc free shuttle is counter-productive to regional transit coordination and integration as championed by Seamless Bay Area. Oakland would do better to coordinate with AC Transit to improve bus service in San Antonio prior to and when San Antonio BART opens.

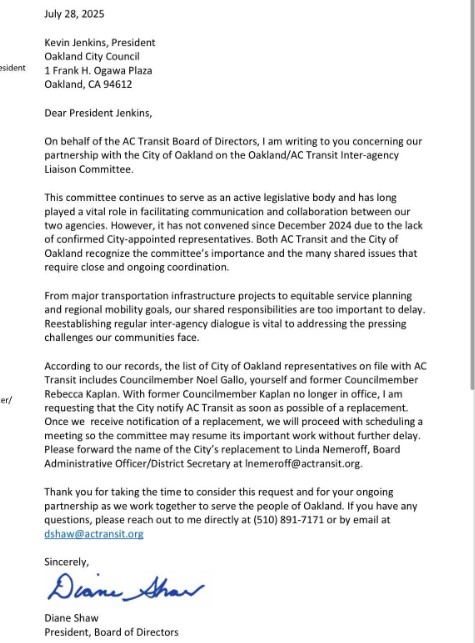

Unfortunately, as noted in a recent letter by AC Transit Board President Diane Shaw to the City of Oakland the Oakland – AC Transit Inter-Agency Liaison Committee has not met for eight months – December 2024 through July 2025 – because Oakland City Council has not named representatives and as a consequence the body has lacked a quorum.

Letter from AC Transit President Diane Shaw to Oakland Council President Kevin Jenkins, dated July 28, 2025

The City, likely in response to the transport planning failures for Brooklyn Basin, proposes to public car parking for a Midtown Waterfront open space as a condition for the new housing and job space there. The failure to provide protected bike lanes and safe pedestrian infrastructure as well as bus service along Embarcadero has led to much frustration with the perceived lack of parking space near Township Commons park.

Off-street parking is an extremely inefficient and expensive mode of providing access to public spaces: even surface parking costs thousands of dollars to create a space that might give access to just a few people per day, not to mention the opportunity cost of taking up that land. Policies that force renters and businesses in future buildings to pay for public off-street parking spaces will drive up costs of living and the cost of doing business compared to focusing on delivering active transportation infrastructure and coordinating with transit agencies to deliver regular transit service. Critically, the proposed strategy doesn’t resolve transport issues but does add more congestion and potential modal conflicts. Planners should focus on actual transport planning within the public realm rather than giving up and demanding private development to pay for public car storage.

Oakland Planners making new tenants and businesses pay for failure to deliver transportation planning.

The Ugly

How will the City of Oakland implement any of this?

It’s not an idle question. Oakland has a particular difficulty delivering public infrastructure:

- Parcel 4 (1911 Telegraph) a 1.04 acre site next to the Fox Theater and 19th Street BART has been vacant for nearly 25 years. The City has tried to develop it in that time period at least three times. The 2014-2017 attempt failed after 1) the City tried to overspec the RFP to require a laundry list of uses like hotel, office space, BMR housing and market-rate housing instead of focusing on a particular priority; 2) the City Council meddled in the RFP process per the Alameda County Grand Jury.

- The Ridge at 51st and Broadway is a 3.5 acre corner vacant site in Rockridge next to a Safeway shopping center. Despite many community groups, electeds and even some local NIMBYs have expressed support for adding housing to this site, the property owner has refused to go along with City’s desires to re-zone the site to allow for housing. The City has been unwilling to explore more forceful planning measures, including eminent domain, in order to deliver housing in this high-resource neighborhood. The Alternatives peg the site for lots of housing growth – what is the City prepared to do to make that happen?

- Estuary Park is currently embroiled in a dispute as landowner Signature Development has expressed interest in developing townhomes key-adjacent land previously slated for park dedication. But this crisis may have been averted had the City not fired its consultant design team 5 years ago (after they produced design concepts and done community engagement) in order to re-procure a new design consultant. At least part of this failure was the city’s acceding to complaints by older park advocates opposed to Estuary Park concepts that included soccer fields and other sports space rather than their preferred non-programmed open space. This self-imposed wasted contract and delay of at least 3 years gave Signature Development the opportunity to initiate the rug pull that is currently coming to head.

- A decade-long promised dog park at Astro Park was permanently shelved in 2012 when Mayor Jean Quan refused to break a tie vote at City Council on whether to move forward with the project over the objections of nearby homeowners and business owners. This effectively killed the project and today many dog owners freely run dogs off leash at Lake Merritt and elsewhere.

- Measure DD promised multi-use path connections from Lake Merritt to the estuary and Bay Trail gap closures along the estuary. Despite spending millions on planning and design consultants for conceptual plans for this infrastructure the City has failed to move them forward for at least a decade. There have been jurisdictional permitting challenges for these projects as they negotiate freeways, utilities and property owners. But City staff have de-prioritized investment in these multi-use path projects at the behest of the citizen architects of Measure DD (CALM and the Measure DD Oversight Committee) who prefer to further invest in Lake Merritt rather than connecting East Oakland to the Lake.

- Oakland’s infrastructure costs 1.5-2x that of peer jurisdictions. Many of these costs are the result of policies and procedures adopted by the City that unwittingly create delay, reduce competition, and impose low to no value contracting requirements. There has been limited improvement on this front recently.

- The draft Oakland Public Lands Policy, which would allocate surplus lands for housing development, has been essentially frozen since 2018. Although some parcels have been floated for development on an ad hoc basis there continues to be indecision by successive administrations and City Council as to what to do with surplus public lands.

Why has Oakland failed to deliver public infrastructure?

No mayor, city council person, staff has spoken about this pattern of implementation failure. To the extent external stakeholders such as community groups, labor, media or Alameda County Grand Jury have noted this dysfunction it is often limited to a particular example.

The pattern that emerges from publicly available information indicates a few conditions driving failure

First, siloing of subject matter expertise into various departments means decisions and actions to drive projects forward are slowed through various internal reviews and validations. While Parks Recreation and Youth Development may be the ultimate client for delivering Estuary Park much of the decision making on planning, transportation, public works, contracts are deferred to other departments. This slows the ability to drive forward development and delivery.

Second, the lack of a clear, empowered project delivery lead means that no one is empowered to say “no” when other departments try to expand the scope beyond the core program objectives. Parcel 4 – 1911 Telegraph may have been originally intended as a housing site but the institutional fragmentation of project delivery allowed Economic Development to insist on office and hotel space, Housing and Community Development to insist on a significant affordable component, Real Estate to argue for highest and best use to realize high rent, and Parks, Recreation and Youth Development to argue for more open space. Without a clear administrative lead empowered to say no to scope creep, the RFP for Parcel 4 was doomed to failure as one 1.04 acre site could not accomplish competing and sometimes mutually exclusive goals.

Third, the City Council requires projects to be brought back to their attention and for their blessing over and over again through program development and project delivery life cycle. While providing democratic input and oversight is important it’s not clear that a half dozen trips to city council is the best way to achieve this. Each trip to the City Council takes up to 6 months and requires significant staff time. That time has the tendency to increase construction costs through escalation, freezes project development while a decision is pending and consumes staff time that could be used for other projects. City Council input and oversight is valuable for setting programmatic goals, providing feedback on conceptual designs and final project approval. For activities like applying for a state grant, procuring a design consultant or awarding a construction contract it’s less clear whether the time and money penalty of City Council approvals is worth it. Indeed as evidenced by the Alameda County Grand Jury’s work on Parcel 4, E. 12th RFPs and public works contracts, some of these trips to City Council tend to provide opportunities for councilmembers to improperly interfere in procurement and contracting.

What can Oakland do to actually implement the General Plan?

Create an Oakland Development Team (ODT) charged with planning and delivery of infrastructure and parks to realize the General Plan.

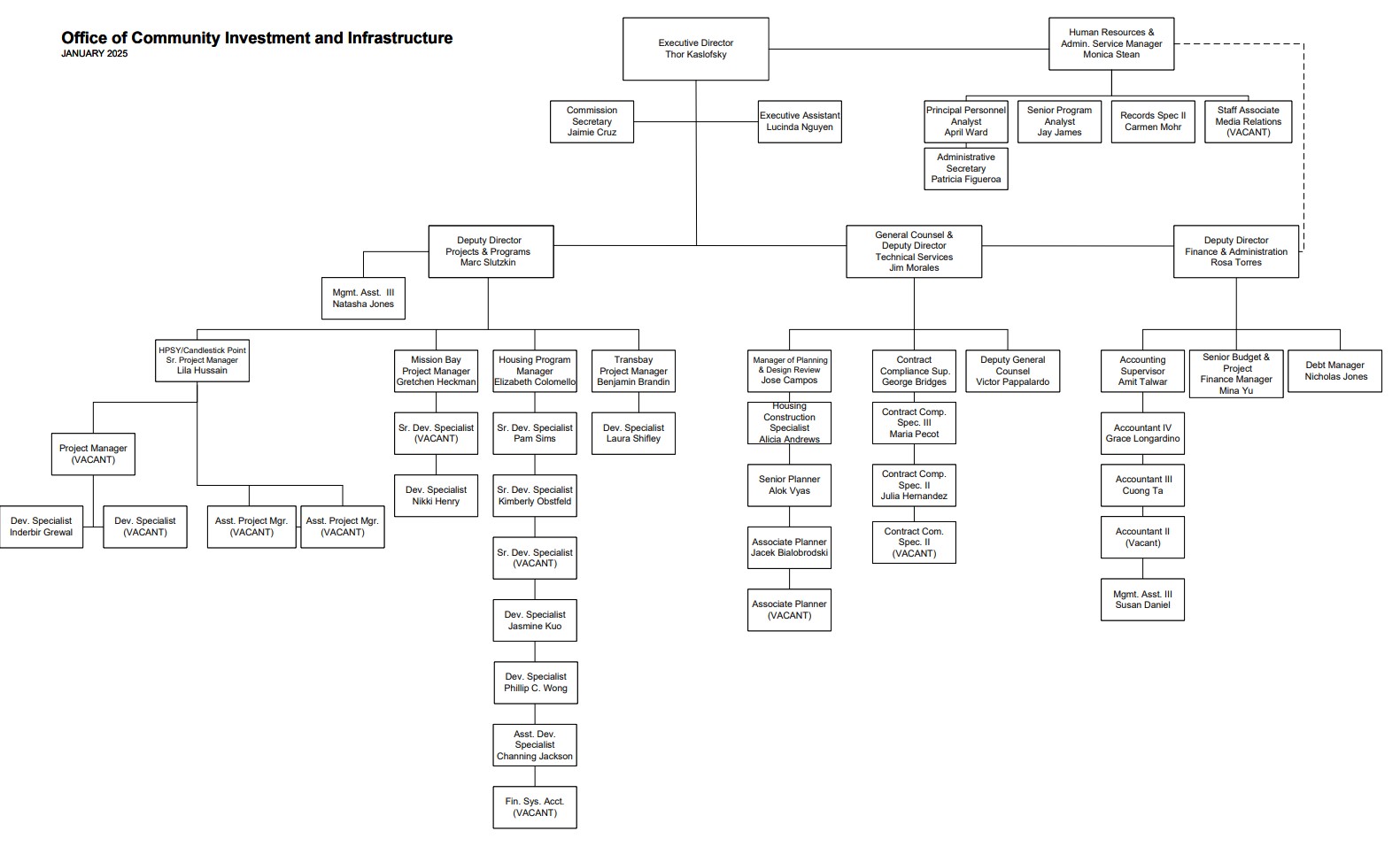

This team would be cross discipline: real estate, planning/design, economic development, transportation, procurement and project management. This is how cities in developed countries throughout the world improve urban neighborhoods. You don’t have to go to France for an example. Seven miles from Oakland the San Francisco Office of Investment and Infrastructure is leading the development of parks, infrastructure and affordable housing in formerly industrial neighborhoods – just like parts of the Midtown Estuary.

Org chart for San Francisco’s Office of Investment and Infrastructure

The ODT should focus on the low hanging fruit by delivering pocket parks first. Can we deliver 5 pocket parks in underserved parts of Oakland in 5 years? Can we leverage existing tax-foreclosed properties themselves or through land swaps to deliver open space for communities?

To meet park needs beyond these assets City Council could provide a programmatic budget over a fixed term to acquire and improve parks. As the ODT delivers open space, it can move up to more complex projects like acquiring the Ridge, developing a San Antonio BART station, redesigning streets for the Midtown Waterfront district and Victory Court. Once the ODT has a proven track record of delivering small projects it can scale up program funding, including construction funding, through City sponsored Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts, revenue bonds, general obligation bonds, land value capture and regional/state grants.

This is simply a proposal. Reform to the City’s implementation of public infrastructure can take many forms. But such reform is a pre-condition to realizing any of the scenarios within the General Plan Alternatives. Otherwise the flashy renderings of new parks, affordable homes and safe streets will not come to fruition but remain stuck in aging PDFs.